The Japanese culture and mythos have been a popular topic for debate for quite some time now, especially with how much of it they portray through their various media outlets.

And while we do have to agree over just how entertaining learning about these gods and goddesses can be, we do have to make a clearcut distinction between the Japanese mythos and the Shinto mythos.

What we mean by that is that most of the mythology and pantheon that you can find under the Japanese label is derived from the traditional stories of the Shinto.

Shinto is one of the main religions of Japan, but it is not the only one. There is also Hinduism and kami-no-michi, or “the Way of the Gods”.

The reason as to why they coexist with one another so successfully though is the fact that they are all polytheistic religions that that were created from the highly pluralistic culture of Japan.

In simpler terms, Shinto is just an evolution of the beliefs of Yayoi culture, which existed predominantly between the years 300 BC and 300 AD, after it was exposed to both Buddhism and Hinduism.

On top of that, the Gods and the Goddesses themselves appear to be inspired by the Kami – or the mythological creatures and spirits that roamed the lands here.

Interestingly enough, it is believed that the very first documentation that specifically mentioned the pantheon dates back to the early 8th century.

While it is a bit of a crude display, it will serve as the first standardized template of the Shinto pantheon that would spread like wildfire around Japan.

But even so, it is pretty much widely accepted that most of the narratives behind these mythological beings are derived from the codified books known as Kojiki, Nihon Shoki and Kogoshui.

Now that we know that much, how about we dive headfirst into the 15 most important Japanese Gods and Goddesses from the aforementioned pantheon, starting off with:

1. Izanami and Izanagi

Most polytheistic religions out there have primordial gods, but very few of them are as well documented or interesting as Izanami and Izanagi.

Their names alone give us a lot of insight into their role in the pantheon, as Izanagi stands for Izanagi no Mikoto, or “he who invites” and Izanami which stands for Izanami no Mikoto, or “she who invites”.

The two brother and sister worked together in order to bring order to the sea of chaos that resided below heaven. In order to do this, they created the first landmass, which ended up as the island of Onogoro.

In some versions it is believed that they were also told to do so by an earlier generation of kami, or divine beings.

Regardless, Izanami and Izanagi ended up creating most other divine entities, as well as the principal eight islands. Later on down the line Izanami would die giving birth to the Fire God known as Kagutsuchi and be sent to the underworld, or Yomi.

2. Amaterasu

Often times cited as the Queen of Heaven or the Japanese Goddess of the Rising Sun, many people believed that the Imperial Family of Japan were direct descendants of hers.

She is believed to have been one of the most important deities in the Shinto religion, being the daughter of Izanami and Izanagi and the ruler of the sky. She is also known for having exiled her brother from heaven for his misdoings.

3. Tsukuyomi

The Moon God Tsukuyomi is a direct descendant of Izanagi that washed away from his right eye after he unsuccessfully tried to save his sibling from Yomi.

Tsukuyomi would end up marrying Amaterasu, which is why it is believed that the Sun and Moon share the same sky in Japanese folklore.

But regardless, Tsukuyomi is known for being very brash and violent, which would eventually end up being his downfall with him killing off Uke Mochi.

After this deed, Amaterasu would end up separating from him, which is why, according to Shinto beliefs, day and night can never coexist with one another.

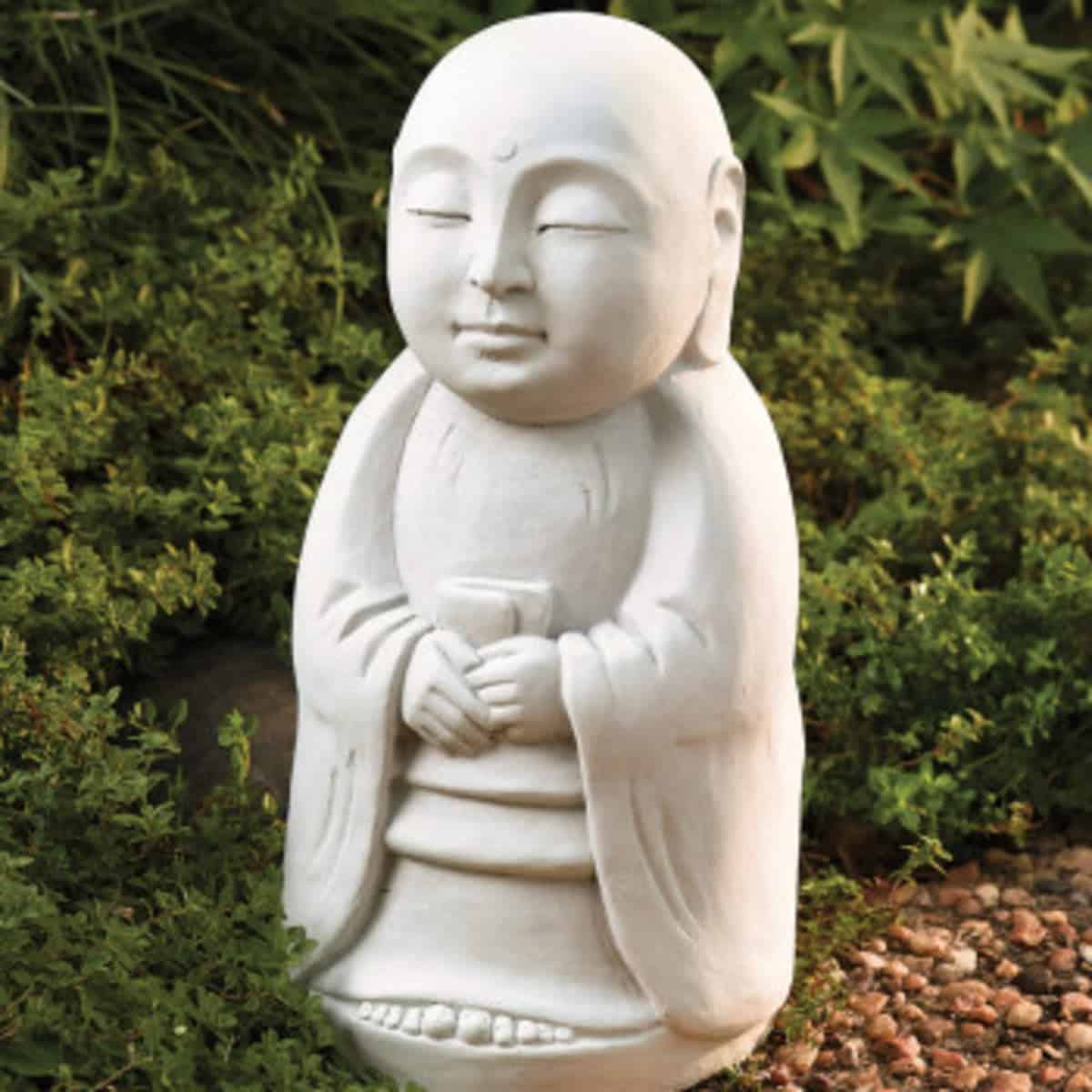

4. Jizo

Jizo is known as a Ksitigarbha outside of Japan, and he is a Bodhisattva, or a practitioner of Buddhism that has created his very own way towards enlightenment in order to help others along the path. As such, you can find plenty of small statues of Jizo around temples.

On top of that, it is believed that Jizo is a guardian of children, especially towards children that died before their parents. He helps them cross the Sanzu River to reach the afterlife.

He also hides them in his robes and crosses in order to make sure that they are saved from an eternity of piling rocks on the riverbank.

In most temples you will see Jizo statues being adorned with small toys, bonnets and bibs. If you are a tourist, we urge you that you do not touch them or move them because they were put there by grieving parents. You may also find plenty of statues of Jizo around graveyards.

5. Inari

Inari is known as the god of rice, sake, tea and prosperity. This kami usually takes on the form of a white or dark-colored fox, but in some iterations, it can also be seen as a woman holding rice in her palms.

This is why if you’ve ever been to a Japanese temple, chances are that you found a series of fox statues that surround a shrine.

Inari may also be seen sometimes as a male, but in most cases, they are meant to represent the farmer or the working individual that puts food on the table.

This kami is known as a benevolent deity that helps those that work hard to feed their families. They are also associated with several other benevolent spirits such as Hettsui-no-kami, or the goddess of the kitchen and the Uke Mochi, or the goddess of food.

6. Kagutsuchi

As mentioned previously, Kagutsuchi is the God of Fire, and he is the son of the primordial kami Izanagi and Izanami.

He is so powerful that when he was born, he burned a hole through his mother which in turn led to her death.

Seeing this happen to his wife, Izanagi ended up lopping off Kagutsuchi’s head, spilling his blood everywhere, which will lead to the creation of even more gods.

As such, although inadvertedly, Kagutsuchi would end up as the creator of several of the most powerful deities in the Japanese pantheon, including the martial thunder gods, the mountain gods and the dragon god.

Because most of the buildings and structures in Japan were made out of wood, the Fire God was feared by all as he was said to have been the most monstrous kami around.

In order to keep him at bay, the Japanese people would undergo several appeasing rituals, including one pertaining to the Ho-shizume-no-matsuri, which is meant to ward off Kagutsuchi’s destructive powers for six months at a time.

7. Raijin and Fujin

Raijin is known as the god of lightning, thunder and storms, while Fujin is the god of wind. The two are almost always seen together, with Raijin carrying a hammer and being surrounded by drums while Fujin carries a bag full of wind.

Interestingly enough, Raijin and Fujin are not seen as good nor bad by most of the Shinto practitioners. Instead, they are both worshipped and feared as they can either be cruel or bountiful to the harvest.

They are also believed to have been the protectors of Japan during the Mongol invasions as they were believed to have been responsible for the kamikaze divine wind that repelled the Mongols in 1281.

So, while not inherently good nor bad, they can be seen standing guard in front of both Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples around Japan.

8. Hachiman

You may have heard of Hachiman, or maybe you heard of him under one of his other nicknames that he received over the years such as Yahata and Emperor Ojin. Regardless of what you know him as, one thing is for certain, Hachiman is not one to be taken lightly.

That’s because Hachiman is known as the God of War in the Japanese mythos, being revered both in Shinto and Buddhism in early medieval Japan.

He is often times portrayed besides the Imperial Family, being considered a protector of theirs and a warrior for their cause.

He is also believed to have helped save Japan during the Mongol invasions by attacking the enemies with a typhoon that nearly destroyed their fleet in one swoop. This later became known as the Kamikaze, or the Divine Wind.

9. Kannon

Kannon is actually one of the most important Buddhist deities in Japan. He/she is worshipped as the God of Mercy, compassion and pets, and they are also meant to represent the aspect of child-giving and loving mothers.

Depending on which religious denominations you go for, you may find yourself confused over what her role is in the world.

In Shinto for example Kannon is a male deity, being the companion of Amaterasu in most texts as he is meant to be the direct opposite of Amaterasu’s former partner, Tsukuyomi.

In Christianity on the other hand, they are revered as Maria Kannon, which is supposed to be the equivalent of Virgin Mary.

10. Susanoo

Susanoo is the brother of Amaterasu and Tsukuyomi, and he was born directly from the nose of Izanagi after his father’s failure to save his mother from Yomi.

As the God of Seas and Storms however, he does not share in their benevolence as he is known to be the most temperamental and violent of the trio.

He has chaotic mood swings, but even so he is still celebrated as the guileful champion that managed to take down the evil dragon known as the Yamata-no-Orochi.

After he prevailed in the battle, he managed to recover his famous sword Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi and he would end up marrying the woman that was held captive by the dragon.

The most popular tale regarding Susanoo though comes to us from his rivalry with Amaterasu. The two would often times challenge each other to see who was the stronger of the two.

On one occasion though, things got a little too hectic as Susanoo would end up destroying the sun goddess’s rice fields and killing one of her attendants.

This led to Amaterasu retreating into a dark cave, essentially robbing the world of her divine light. In retaliation, Susanoo would end up leaving heaven altogether.

11. Ame-no-Uzume

Ame-no-Uzume is the Goddess of Dawn and Dancing, and she is most often times portrayed as the assistant of Amaterasu. She is meant to represent the spontaneity of nature.

On top of that she is also an avatar of the arts and crafts, dancing and creativity, and she is believed to be a part of the central myths that revolves around Amaterasu in the Shinto beliefs.

As mentioned previously, after being driven away by Susanoo, Amaterasu locked herself in a dark cave, which resulted in a period of darkness enveloping the earth.

In order to make her days more joyful and to help get her out of her self-inflicted confinement, Ame-no-Uzume would end up covering herself in the leaves of a Sakaki tree, making cheery cries and dancing in front of the gods while hoping to get Amaterasu’s attention.

She would even end up taking off her clothes as she would continue to dance in front of the gods, making them all howl with laughter and joy.

Wanting to see what the fuss was all about, Amaterasu would end up coming out of her cave, bringing light back to the world.

12. Yebisu

Yebisu is known as the God of Luck and Fishermen, which is quite funny considering the fact that his early beginnings were anything but lucky.

When he was born, he was known as Hiruko, or the Leach Child, and he was the first child of Izanagi and Izanami.

His body was deformed beyond reason, lacking bones and thus being unable to move around freely. As such he was thrown out into the sea at the age of three.

His life would soon change however as due to sheer luck alone he would wash up ashore to one Ebisu Saburo.

After growing up, he decided to call himself Ebisu or Yebisu, becoming known as the god of fishermen, children and wealth/fortune.

What is most popular about Yebisu is the fact that he never cried because of his misfortune, always laughing joyfully in the face of adversity, coming out on top by the end of every trial.

As such, he is also referred to as the the Laughing God and he’s usually portrayed wearing a tall and pointed hat that’s folded in the middle.

13. Tengu

Tengu may not be kami themselves, but they are considered to be some of the most important figures in the Shinto pantheon.

They are bird-like creatures that have long red noses and are known for being extremely skilled both with their blades and with their magic.

On top of that they can fly around with ease and are quite proficient when it comes to the martial arts. Even though they used to be known as adversaries of Buddhism at first, they would eventually become its protectors.

Even so, seeing a Tengu is considered to be a sign of misfortune, as they love tricking humans and making them stray away from the path of Buddhism as a test of their beliefs.

14. Benzaiten

Benzaiten, also commonly referred to as Benten, is a Buddhist deity that is meant to represent the arts and femininity.

As such, she was the main source of veneration for geishas. She is said to have been the most beautiful figure in the world, and she is also the only female in the Seven Gods of Fortune lineup.

She is often times cited as the goddess of luck, and she is usually portrayed riding a large sea dragon while playing her biwa.

She was so beautiful in fact that according to the mythos, she even managed to tame a five-headed dragon by simply showing the monster her beauty.

You can find a temple that was erected in her name in Enoshima called the Ryuko-Ji, or the Dragon’s Mouth Temple.

15. Anyo and Ungyo

Anyo and Ungyo are known as the benevolent guardians that protect the entrance of Buddhist temples. They are meant to represent the birth and death cycle.

Anyo can usually be seen portrayed bare-handed or with a massive club in his hand while Ungyo usually has a large sword but can also be seen sometimes bare-handed.

Another way to differentiate between the two is by looking at their mouths, since Anyo’s mouth is open and Ungyo’s is closed. That’s because Ungyo’s mouth is meant to form the sound “om” which represents death.

Even though they can be found all throughout the country, by far their most famous depiction can be found at the entrance of the Todaiji Temple from the Nara Prefecture.

Conclusion

Japan really is one of the most fascinating places you could ever go to if you have a knack for mythology now, isn’t it? Its pantheon is full of gods and goddesses with each and every one of them having their very own trials and tribulations that they had to go through.

Regardless of whether you’re interested in the Shinto, Buddhism or kami-no-michi beliefs, there are more than enough legends and fables for you to get drawn into.

But thank you for reading this far and we hope that this article helped you better understand the pantheon of gods, deities and kami that the Japanese culture has in store for us.